Cave in for Later

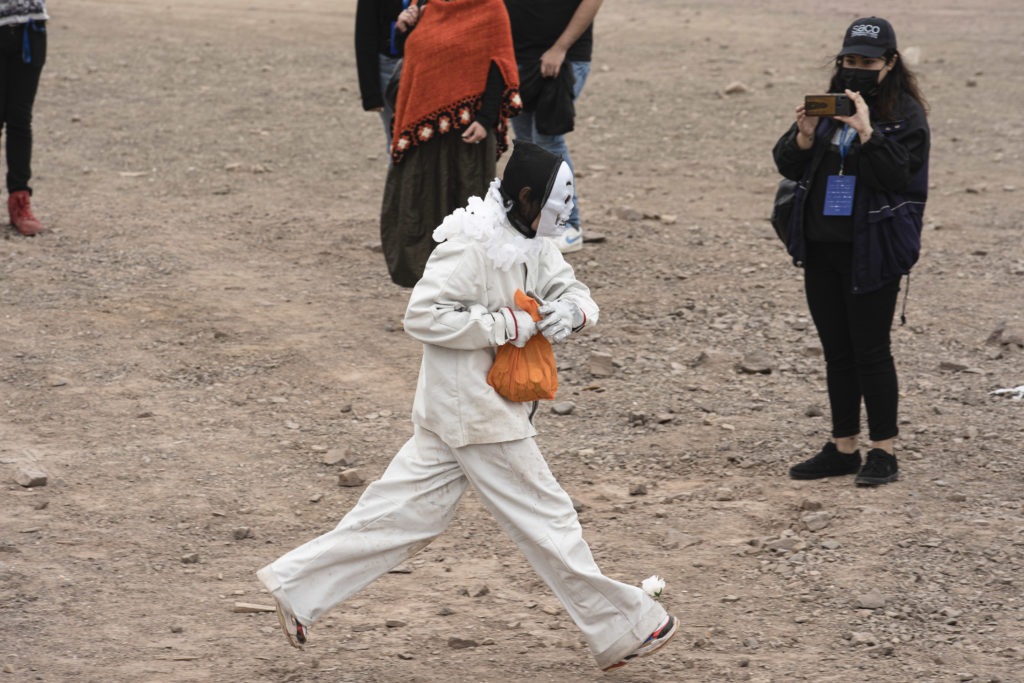

2021 Performance & Site specific installation

Saco Biennale Antofagasta, Chile

Photo credits : Kinga Olesiejuk & Biennale Saco

Avec le soutien de la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles International

The focus of the 2021 Saco Contemporary Art Biennial was ‘Flood’ – in memory of the 1991 floods that devastated Antofagasta, a city that borders the Atacama Desert. An invitation to reflect upon the permanent possibility of imminent catastrophe, and how humanity would overcome it – if at all. Thanks to the Federation of Wallonia-Brussels, I was invited to propose a project.

While browsing through Wikipedia, I discovered Tapu, an ancient ritual from Rapa Nui. Tapu was a way to prevent the depletion of natural resources, by means of local and temporary prohibition of their use. Despite its technological advances, our civilisation has completely lost this kind of pragmatic consideration. In a contemporary reflection on this ritual, I imagined burying several refrigerators in the desert.

After my project proposal had been selected, the organizers of the Biennale Saco shared an urban legend with me, according to which a child survives the floods by hiding in a fridge. I knew nothing about it, but was pleasantly surprised by the overlap between this tale and my initial idea. The location for my intervention is the site of the ruins of Huanchaca, a former silver foundry.

I put myself in the skin of this child, sole survivor, plays to ward off death by disguising himself as a skeleton. He was forced to bury his relatives – or rather the values that eventually caused them to perish (more details on this later).

The surviving child gathers in front of the graves and offers them a drink from the precious few bottles of soda that are left. He’s sowing what seem to be the remains of the economy, hoping to bring back abundance: he’s throwing chocolate coins around. The slightest signal makes him run away and hide in his fridge.

In working towards my performance, I integrated the following objects:

–

a piece of fichas – a rubber coin that was used to pay miners, and was

an effective way to enslave them through a restricted circuit of the

economy. the can still be found at the small port of Antofagasta for

3000 pesos each;- 3-litre bottles of soda that is cheaper than water. In the shops, you can contract localized credit. Everything is privatized in Chile, and hence debt is omnipresent;

–

artificial flowers: they are widely found in Chinese shops, and they

are used to decorate the graves of animals, and animitias – small

temples to honor the victims of road accidents;

– low value coins, and chocolate coins wrapped in bad imitations of euros;

– an overall in white leather, a piece of workman’s clothing that I found at the flea market.

Cette année, la biennale d’art contemporain Saco avait pour thème « Aluviòn » – inondation – en souvenir de celles qui avaient dévasté la ville d’Antofagasta en 1991, située aux portes du désert d’Atacama, l’un des plus secs au monde. Une invitation à considérer la possibilité d’une catastrophe imminente et comment l’humanité s’en sortirait, ou pas, cette fois. Via la Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles Internationale, j’ai été invitée à proposer un projet.

En dérivant sur Wikipédia, j’ai découvert le « Tapu », un rituel ancien originaire de Rapa Nui (j’ignorais auparavant que l’île de Pâques faisait partie du Chili, la géographie n’a jamais été ma grande spécialité). Le Tapu consistait à interdire la consommation de certaines denrées afin d’éviter l’épuisement des ressources. Notre civilisation pourtant bien plus avancée technologiquement, a totalement perdu ce genre de considération pragmatique. J’ai pensé à enterrer des frigos dans le désert, couchés comme des tombes.

Après avoir sélectionné mon projet, les organisateurs de la Biennale Saco m’ont raconté une légende urbaine selon laquelle un enfant aurait survécu aux inondations en se cachant dans un frigo. Quelle incroyable coïncidence, qui devient immédiatement un ingrédient dans ma recherche. Le lieu qu’ils choisissent pour mon intervention se situe auprès des ruines de Huanchaca, une ancienne fonderie d’argent. Je me suis mise dans la peau de cet enfant, l’unique survivant qui joue à conjurer la mort en se déguisant en squelette. Dans ma version, il a été forcé d’enterrer les siens ou plutôt – les valeurs qui les ont perdus. Les frigos sont devenus des tombes où sont enterrés : le romantisme créateur, la valeur-travail et l’obligation de gagner de l’argent, l’innocente compagnie des animaux (qui en cas de famine, se nourriraient rapidement de nous), le tourisme à l’aveuglette. L’enfant survivant se recueille devant les tombes et les abreuve avec les précieuses bouteilles de soda qui lui restent. Il sème de la monnaie, en croyant faire revenir l’abondance. Au moindre signal, il retourne se cacher dans son frigo.

Sur mon chemin, j’ai intégré les objets suivants :

– une pièce de fichas, monnaie en caoutchouc utilisée pour payer les mineurs et façon de les esclavagiser par un circuit restreint de l’économie, qu’on peut encore acheter au petit port d’Antofagasta pour 3000 pesos pièce.

– des bouteilles de soda de 3 litres, qu’on peut acheter par 3 au supermarché, à un prix plus bas que l’eau. Au supermarché, on peut contracter un crédit localisé. Tout est privatisé au Chili, la dette est omniprésente.

– des fleurs artificielles : on les trouve à foison dans les magasins chinois, elles sont utilisées pour décorer les tombes d’animaux entre autres, et les animitas, petits temples pour honorer les morts par accident le long des routes

– des pièces de monnaie de faible valeur et des pièces en chocolat, mauvaise imitation des euros

– un ensemble en cuir blanc, un vêtement de travail trouvé au puces d’Antofagasta

– un dinosaure à deux têtes en plastique